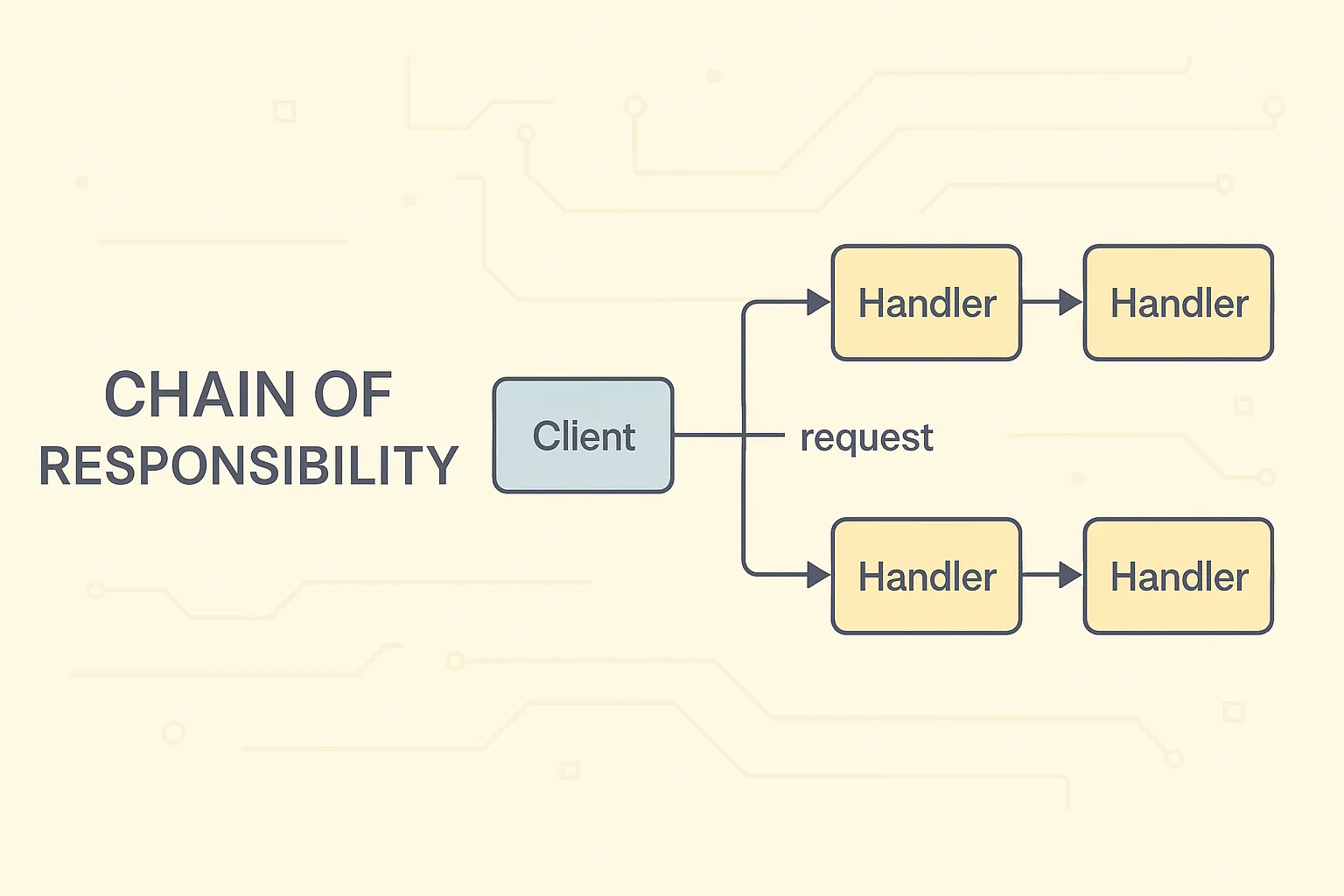

the Chain of Responsibility (CoR)—that allows a request to pass through a sequence (or pipeline) of potential handlers. Each object in that sequence (like middleware components or approval stages) decides whether to act on the request or pass it along.

🧠 What is the Chain of Responsibility Pattern?

The Chain of Responsibility (CoR) pattern is a behavioral design pattern that enables you to pass a request along a chain of handlers. Each handler in the chain decides whether to handle the request or delegate it to the next handler in line.

How It Works

- Each handler has a reference to the next handler in the chain.

- If the current handler can't process the request, it passes it forward.

- This continues until one handler handles the request—or none do.

Benefits

- Decouples sender and receiver logic.

- Makes the processing logic extensible and reorderable.

- Promotes single-responsibility and open/closed principles.

🎯 Intent

“Avoid coupling the sender of a request to its receiver by giving more than one object a chance to handle the request.”

🏗️ Structure (UML)

classDiagram

direction LR

class Client {

+request: string

}

class Handler {

+SetNext(handler: Handler): Handler

+Handle(request: string): void

}

class SpamHandler {

+Handle(request: string): void

}

class SupportHandler {

+Handle(request: string): void

}

class FeedbackHandler {

+Handle(request: string): void

}

Client --> Handler : sends request to

Handler <|-- SpamHandler

Handler <|-- SupportHandler

Handler <|-- FeedbackHandler

SpamHandler --> SupportHandler : passes request if unhandled

SupportHandler --> FeedbackHandler : passes request if unhandled

💡 🎧 Customer Support Analogy

To understand the Chain of Responsibility pattern, imagine how customer service works:

- Level 1 Support – Handles basic, frequently asked questions or common issues.

- Level 2 Support – Tackles tickets that require deeper troubleshooting or specialized knowledge.

- Level 3 Support – Reserved for complex technical cases or issues needing expert intervention.

Each level checks whether it can resolve the issue. If it can't, the request is passed along to the next level—just like how handlers operate in a CoR processing chain.

💻 Code Examples

// Handler base class

abstract class Handler

{

protected Handler next;

public Handler SetNext(Handler handler)

{

next = handler;

return handler;

}

public abstract void Handle(string request);

}

// Concrete Handlers

class SpamHandler : Handler

{

public override void Handle(string request)

{

if (request.Contains("Buy now"))

Console.WriteLine("SpamHandler: Marked as spam.");

else

next?.Handle(request);

}

}

class SupportHandler : Handler

{

public override void Handle(string request)

{

if (request.Contains("support"))

Console.WriteLine("SupportHandler: Routed to support team.");

else

next?.Handle(request);

}

}

class FeedbackHandler : Handler

{

public override void Handle(string request)

{

if (request.Contains("feedback"))

Console.WriteLine("FeedbackHandler: Stored in feedback inbox.");

else

Console.WriteLine("No handler could process the request.");

}

}

// Client code

class Program

{

static void Main()

{

var spam = new SpamHandler();

var support = new SupportHandler();

var feedback = new FeedbackHandler();

spam.SetNext(support).SetNext(feedback);

var requests = new[] {

"I'd like to give feedback",

"Buy now! Limited offer!",

"Need help with my account",

"Hello there!"

};

foreach (var req in requests)

{

Console.WriteLine($"\nRequest: {req}");

spam.Handle(req);

}

}

}

class Handler:

def __init__(self):

self.next = None

def set_next(self, handler):

self.next = handler

return handler

def handle(self, request):

raise NotImplementedError

class SpamHandler(Handler):

def handle(self, request):

if "Buy now" in request:

print("SpamHandler: Marked as spam.")

elif self.next:

self.next.handle(request)

class SupportHandler(Handler):

def handle(self, request):

if "support" in request:

print("SupportHandler: Routed to support team.")

elif self.next:

self.next.handle(request)

class FeedbackHandler(Handler):

def handle(self, request):

if "feedback" in request:

print("FeedbackHandler: Stored in feedback inbox.")

else:

print("No handler could process the request.")

# Client code

if __name__ == "__main__":

spam = SpamHandler()

support = SupportHandler()

feedback = FeedbackHandler()

spam.set_next(support).set_next(feedback)

requests = [

"I'd like to give feedback",

"Buy now! Limited offer!",

"Need help with support",

"Hello there!"

]

for req in requests:

print(f"\nRequest: {req}")

spam.handle(req)

🏢 Real-World Use Cases

| Scenario | How CoR Helps |

|---|---|

| Middleware in ASP.NET pipeline | Each middleware can pass to the next |

| Event processing | Pass event to subscribed handlers |

| Approval systems | Tiered approval flow (manager → director → VP) |

✅ Pros and ❌ Cons

| Pros | Cons |

|---|---|

| Reduces coupling | Can lead to unhandled requests |

| Adds flexibility in order of handling | Harder to debug if chain is long |

| Easily add/remove handlers | Requires careful design of handler logic |

🧪 Quick Quiz

📌 When to Use the Chain of Responsibility Pattern

- ✅ Multiple Potential Handlers: When a request might be processed by any of several objects, and you don’t want to hardcode which one.

- 🔄 Decoupled Sender/Receiver: When the object that sends the request shouldn’t need to know which object will handle it.

- ⚙️ Dynamic Handler Chain: When the order or combination of request processors might change during runtime.

These situations are ideal for using CoR to create flexible, pluggable pipelines where logic can evolve without disrupting core functionality.

🚫 When Not to Use the Chain of Responsibility Pattern

-

📣 All Handlers Must Act:

If every handler must process the same request—like logging to multiple sinks—CoR is a poor fit.

// Not suitable: Each logger needs to process the message abstract class Logger { protected Logger next; public Logger SetNext(Logger logger) { next = logger; return logger; } public virtual void Log(string message) { // All loggers log regardless Console.WriteLine($"{this.GetType().Name} logs: {message}"); next?.Log(message); } } -

🐞 Hard to Debug:

When tracing request flow is important, CoR makes things harder because execution jumps between handlers implicitly.

// Debugging this flow gets tricky as requests pass silently abstract class Handler { protected Handler next; public Handler SetNext(Handler handler) { next = handler; return handler; } public abstract void Handle(string request); }Especially in long chains, identifying why a request wasn't handled—or by whom—requires verbose logging or breakpoints.

In these cases, consider Composite or Observer patterns instead, depending on the goal. These allow parallel handling or better event propagation control.

🧭 Final Thoughts

The Chain of Responsibility is perfect for building extensible processing pipelines. From approval systems to loggers and middleware, this pattern offers clean separation and dynamic routing of requests.